Interactive: The European approach to stopping Libya migration

Explore the abusive and deadly effects of EU and Libyan policies in the central Mediterranean.

Design and production by Kylee Pedersen and Marc Fehr.

Eric Reidy

Migration Editor-at-large

Every day last year, more than four people on average died attempting to cross the central Mediterranean from North Africa to Europe, and around 90 were intercepted by the EU-supported Libyan Coast Guard – returned to detention centres where they face a cycleof torture, extortion, and sexual abuse.

This year, with crossings guaranteed to increase in the warm summer months, more than 8,200 people have already been intercepted by the Libyan Coast Guard and nearly 700have died or gone missing at sea.

Year after year, the deaths and interception follow a well-established, predictable pattern. But instead of saving lives or protecting the human rights of asylum seekers and migrants, “European countries have engaged in a race to the bottom to keep people in need of our protection outside our borders,” Dunja Mijatović, the Council of Europe’s Commissioner for Human Rights, wrote in a March 2021 report.

Died/missing in 2021

Intercepted & returned in 2021

That race has involved withdrawing European navy and coast guard assets from rescue activities in the central Mediterranean, obstructing the operations of rescue NGOs, and funding the implementations of border management projects in Libya and Tunisia aimed at preventing people from crossing the sea.

The system that has been created by this process is “one of the most glaring examples of how bad migration policies undercut human rights law and have cost the lives of thousands of human beings”, according to Mijatović’s report.

Asked for comment, Peter Stano, the European Commission’s lead spokesperson for foreign affairs, told The New Humanitarian via email: “Our top priority is saving lives at sea and we will continue our work to prevent these risky journeys from taking place.”

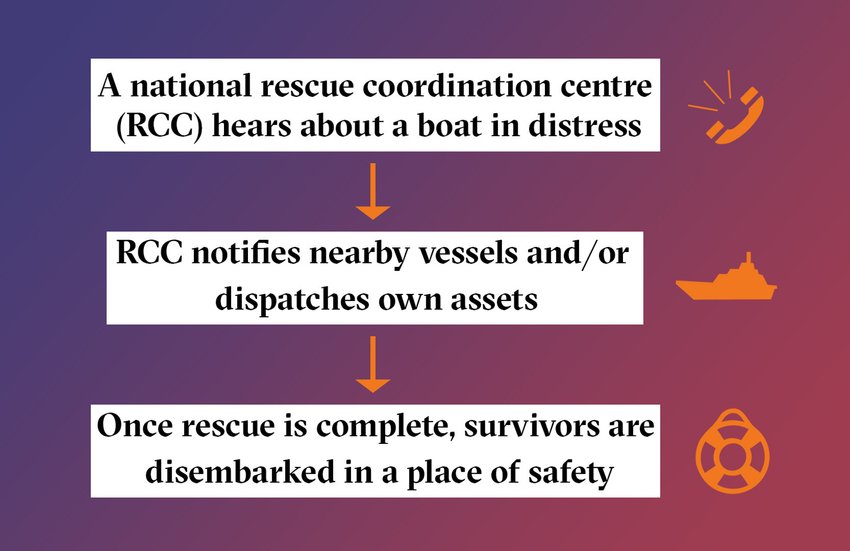

Below, we show how straightforward search and rescue at sea can be. Then, explore the interactive storyline to see how the EU-backed migration control system in the central Mediterranean facilitates more interceptions by the Libyan Coast Guard and reduces search and rescue capacity – increasing the likelihood of shipwrecks and deaths.

How maritime search and rescue is supposed to work:

Now, explore this interactive storyline to see how the EU-backed migration control system in the central Mediterranean responds to boats in distress:

Sara Creta/TNH

The boat is spotted

The boat makes a distress call

Neither of the above

Distress situations at sea are complex, and several of these scenarios can play out simultaneously.

How did we get here?

The situation in the central Mediterranean is “not a tragic anomaly”, according to a recent reportby the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR), “but rather a consequence of concrete policy decisions and practices by the Libyan authorities, European Union (EU) Member States and institutions, and other actors”.

At the height of the Mediterranean migration crisis in November 2015, EU member states laid out an Action Plan for “better migration management” during a summit between European and African countries in Malta, and launched a funding mechanism – the EU Trust Fund for Africa – to finance its goals.

As one of its priorities, the plan called for EU member states and institutions to improve countries’ abilities to “control land, sea and air borders as well as maritime surveillance capabilities for the purpose of prevention of irregular migration”.

To implement this objective in Libya, the EU and EU member states – especially Italy – have spent tens of millions of euros in recent years to:

1.

Provide patrol boats, training, and supportto the Libyan Coast Guard to intercept asylum seekers and migrants at sea – including conducting repairs on donated Libyan Coast Guard boats when they need maintenance.

2.

Guide Libyan authorities through the process of declaring a search and rescue region in the central Mediterranean where Libya has primary responsibility for coordinating the response to boats in distress – this was given international recognitionin June 2018.

3.

Establish a Libyan Rescue Coordination Centre to oversee activities in Libya’s newly declared search and rescue region. Despite the support, human rights groups, NGOs, and journalistssay the official Libyan rescue coordination centre doesn’t actually exist and the Libyan Coast Guard instead receives information about boats at sea via a poorly equipped command centre at a military base in Tripoli.

Since the declaration of the Libyan search and rescue region, the EU and EU member states have helped facilitate the Libyan Coast Guard’s interception of boats in three main ways:

1.

They have gradually withdrawntheir naval and search and rescue assets in the central Mediterranean and shifted responsibility for coordinating responses to boats in distress to the Libyan Coast Guard.

2.

The EU border agency, FRONTEX, has become increasingly active at conducting aerial surveillance to detect the departure of boats carrying asylum seekers and migrants from Libya – at first using airplanes, and switching to high-altitude drones starting in May this year.

3.

EU member states have obstructed the operations of search and rescue NGOs through criminal investigations and administrative procedures that have made it difficult for them to maintain a presence at sea. The most recent audit by the EU’s Agency for Fundamental Rights, in December 2021, found that since 2016 around 35legal proceedings have been initiated against boats that operate in the central Mediterranean, obstructing their ability to perform rescues for varying periods of time.

Stano, the European Commission’s spokesperson, said: “It is unfair and actually incorrect to blame the European Union for the suffering of the migrants trying to cross the Mediterranean from Libya” – pointing instead to smugglers and traffickers who exploit asylum seekers and migrants.

But human rights watchdogs, researchers commissioned by the EU Parliament, search and rescue NGOs, and activistssay Italy, Malta, and the EU border agency seek to make Libyan authorities the first point of contact when boats depart for Europe, cutting civilian rescuers – when they’re able to get to sea – out of communication channels in most cases.

European countries are also slow – and sometimes fail – to mobilise their own search and rescue assets to assist boats in distress. When it comes to Malta, this is true even when boats have entered the Maltese search and rescue region.

As a result, boats of migrants and asylum seekers are being intercepted more often by the Libyan Coast Guard – which has been documented opening fire at, ramming, and capsizing boats it is supposed to rescue.

Those intercepted are pulled back to Libya, where they are automatically detained in official centres rampant with abuse, or disappeared by the thousandsinto shadowy, semi-official facilities where they are beyond the reach of international organisations. The boats that are not intercepted are left to spend a longer time at sea, increasing the likelihood of shipwrecks and of people dying from exposure to the elements.

Since 2017, when the EU and its member states began implementing the action plan for “better migration management”, more than 92,000 people have been intercepted by the EU-backed Libyan Coast Guard, and more than 8,600 others have died or disappeared in the central Mediterranean.

Arrival, interception, and death statistics come from UNHCR and IOM and represent totals as of 15 November 2021.

(This is a republication of a story initially published on 17 November 2021.)

↑ Scroll to top