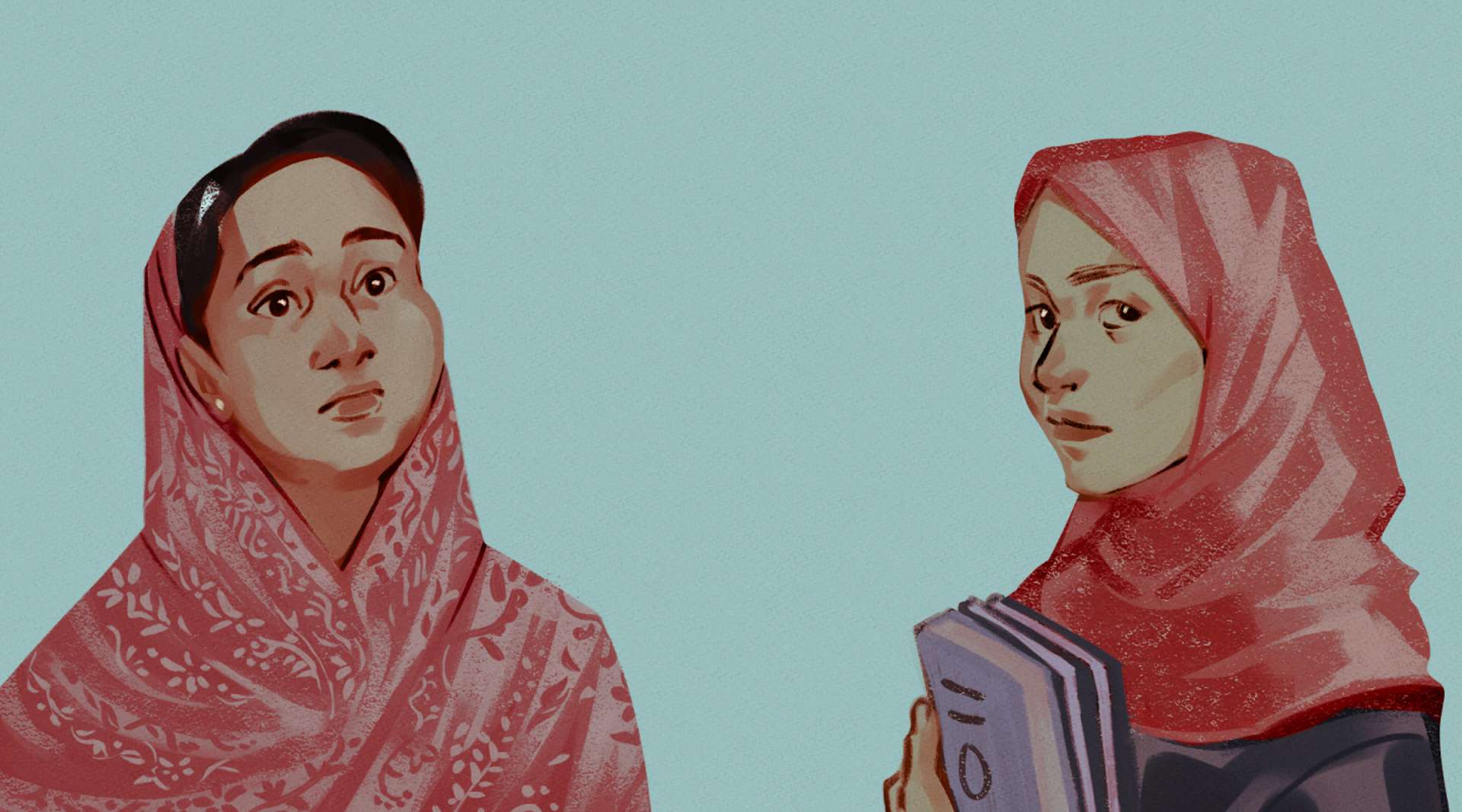

‘I am a leader of my house’

How Romida and Hafsa are pushing for change in the Rohingya refugee camps – while holding on to the hope of returning home.

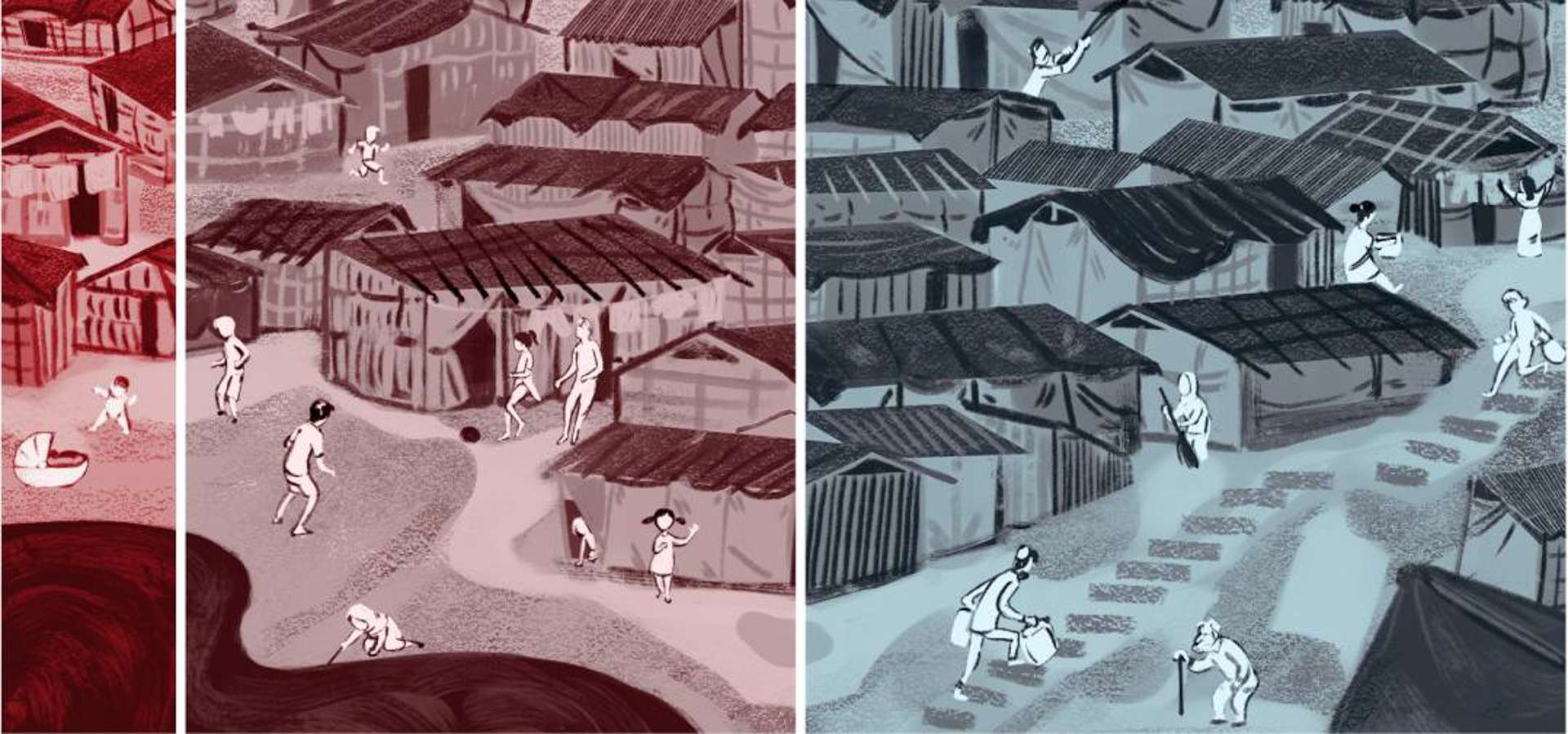

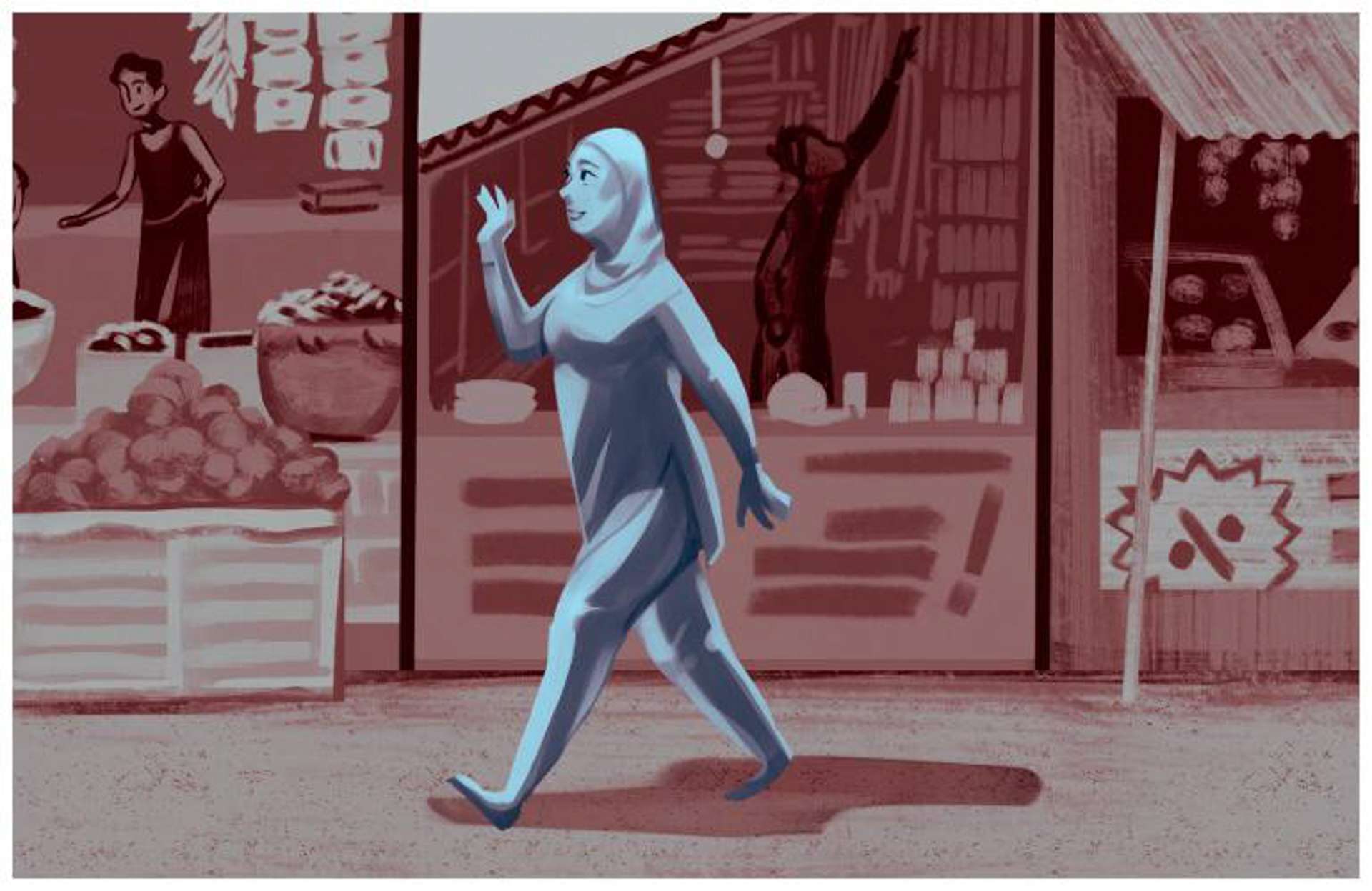

Rohingya refugees have lived in Bangladesh for decades. They fled persecution in Myanmar, including a violent military purge that pushed out hundreds of thousands of people in 2017. As Romida and Hafsa found when they arrived, life in these cramped camps is hard, especially for women and children.

Hafsa: “In Myanmar, women used to live with dignity, but in the camps they are always worried about their safety. Women don’t feel safe anymore – even at home.”

Women and girls live with daily struggles most men don’t have to think about: domestic violence, family restrictions, pressure or even threats from men who don’t think women should work outside the home …

… or simply the dangers of using a toilet at night.

Romida: “We have one toilet for 10 or 20 houses. It’s difficult for unmarried women to go far from their homes to use the toilet. They need to pass groups of men on the way, which is pretty uncomfortable. We fear being attacked when it's dark. There are many problems, especially for women. Domestic violence is a big one, and the fact that there are no jobs for the men – or women – is a huge cause of this.”

Hafsa and Romida want things to be different. They're pushing for better education for Rohingya kids, and helping to give women and girls a voice in the way the camps function.

Romida, 29

Elected Community Leader

“I want to keep the women in my camp safe.”

Hafsa, 22

University student and aspiring teacher and social activist

“I want to ensure graduation for every Rohingya child out there.”

As an elected leader, Romida represents some 16,000 people in one part of the massive camps. She helps resolve family disputes, coaches people on how to prepare for disasters or how to stop child abuse, and tries to make sure things like damaged homes and roads get fixed. In a community often dominated by conservative men, she stands out.

… But some of these men don’t like having a woman in charge.

“We need women in leadership roles to demand this change that we need. Women are happy that they can share problems with me as a lady leader. They are happy to have me, but I don’t know about guys. Majhis* are often not happy to see me as a leader. Ultimately, I want to keep the women in my camp safe: I want to ensure every woman's safety.”

*unelected Rohingya representatives installed by the Bangladesh army.

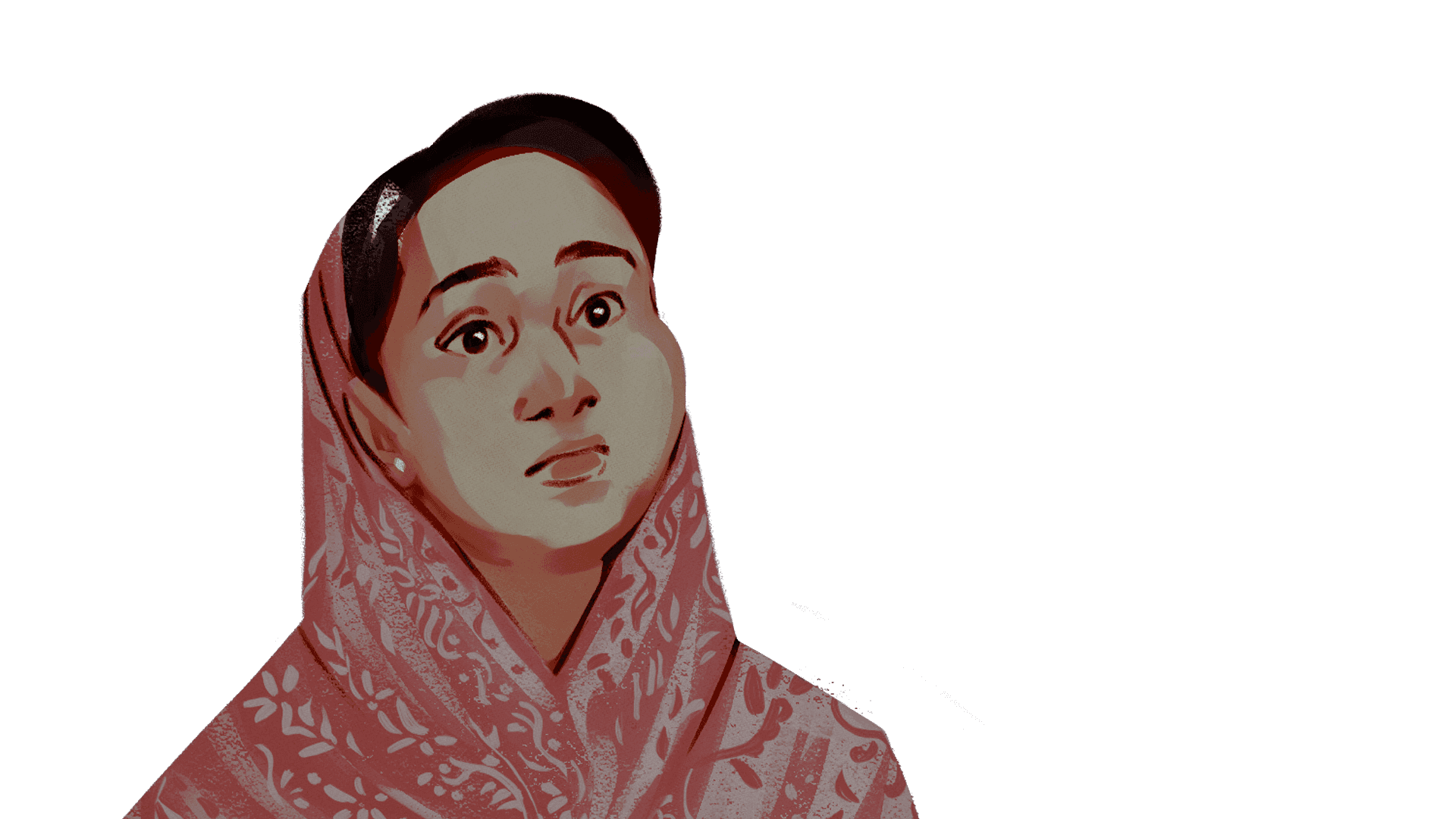

Hafsa stands out, too. She goes to university in the nearby city of Chittagong. In Myanmar, few Rohingya ever make it to university due to deep discrimination and restrictions that prevent many from studying, going to proper hospitals, or simply leaving their villages without permission. Hafsa finished high school but was never allowed to enrol in a university. In Bangladesh, however, she won a rare scholarship while volunteering to work on sexual and gender-based violence for a medical NGO. She hopes to major in politics, philosophy, and economics.

.png)

“Through all of this, I never gave up the dream of studying further. I always wanted to graduate and become a teacher. Eventually, I made my dreams a reality.”

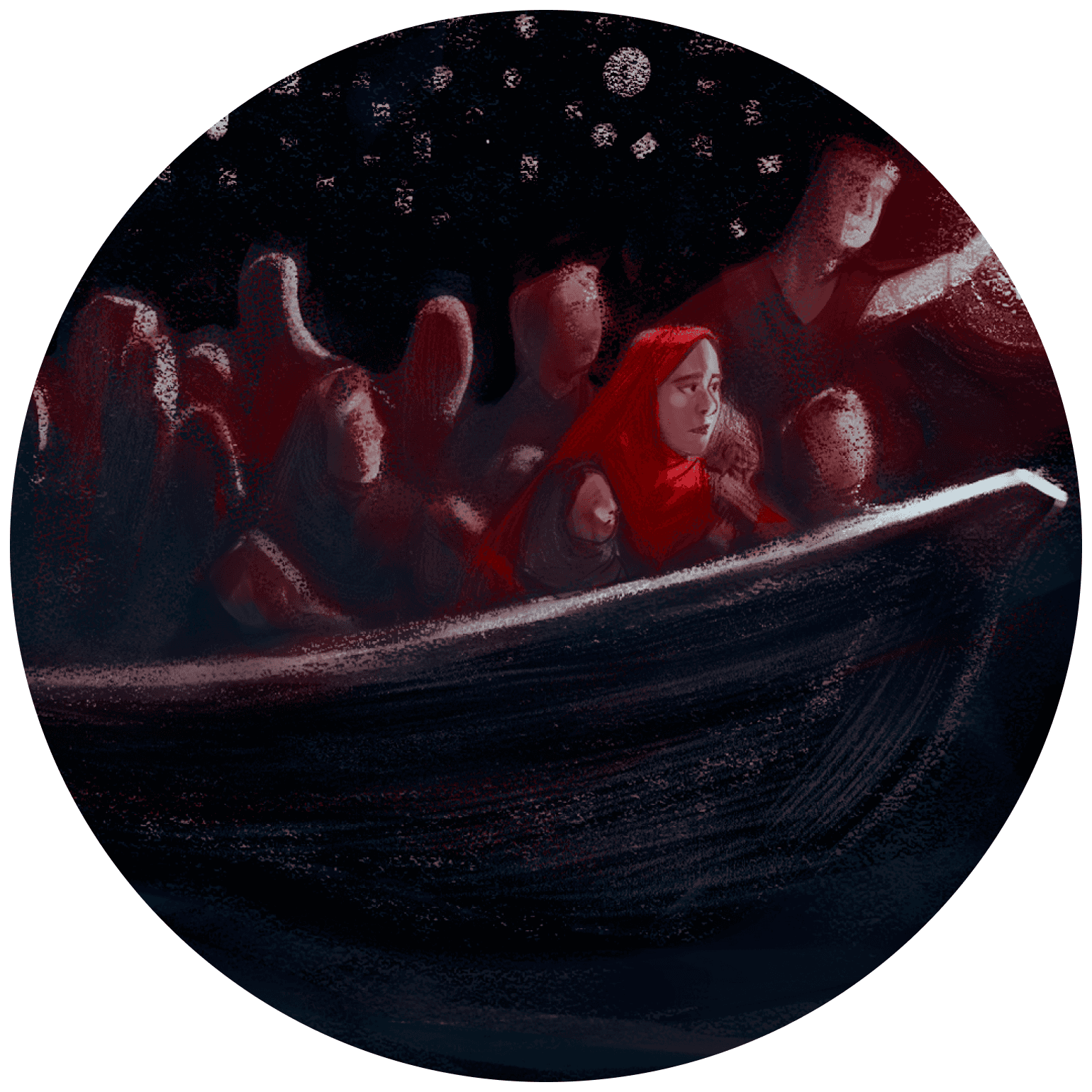

Romida and Hafsa see themselves as leaders, but they never planned for this. They both fled their homes in Myanmar’s Rakhine State during 2017’s military crackdown. UN investigators and human rights groups say the persecution of the Rohingya in Myanmar is part of a decades-long genocide. Government policies and military crackdowns have stripped them of citizenship, thrust apartheid-like restrictions on their daily lives, and expelled them from their homeland.

“The army attacked us and our villages, and we had to leave our homes and country behind.”

“It took 15 days for us to come to Bangladesh by foot and by boat. At one point, I didn’t think that I would make it. My legs were so painful I couldn't walk. I told everyone to go without me. Then someone said the army was nearby; we started running. Soon, we heard gunshots. Two of our relatives died.”

.png)

Within weeks, more than 700,000 people crossed into Bangladesh. Thousands were killed. Families were separated in the chaos.

“We left in a rush – me, my six siblings, and my mother. My father worked in town and we were living in a village. When the military attacks started, we couldn’t get to my father and he couldn’t get to us. Neighbouring areas were also under attack, so we were stuck. My father said we should flee to Bangladesh. So he stayed, and we left…”

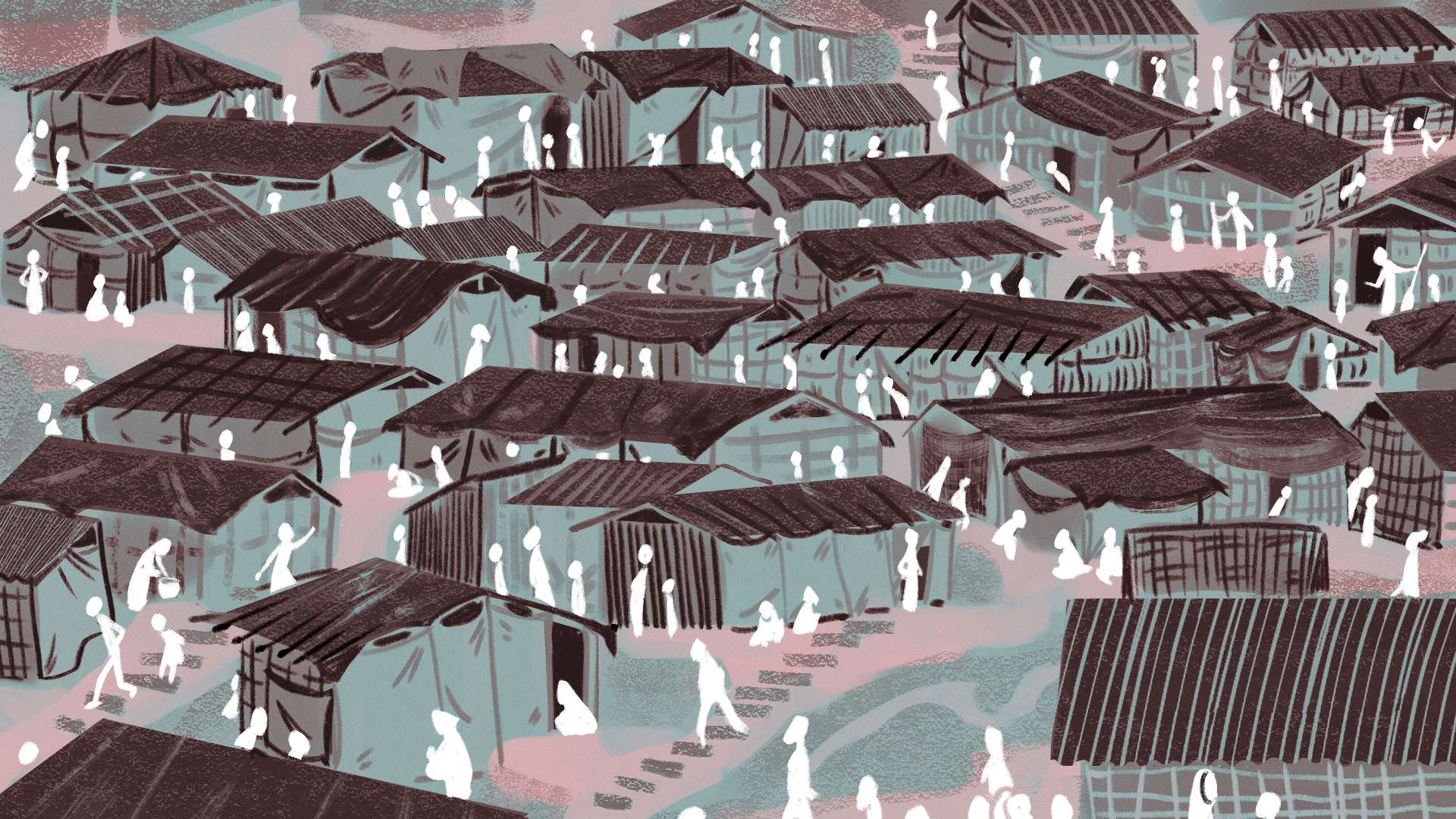

The 2017 crackdown quadrupled the population of Bangladesh’s sprawling camps. Today, some 900,000 Rohingya live here. The vast majority are women or children.

“When we arrived at the camps, everything was messy and horrible. There were no toilets, and no way to purify water for drinking.

When the military attacked us, we thought we would return home soon, so we didn’t take much. I took only my mobile phone. My mother took my education certificates and our family documents.

We didn’t have enough clothes to wear. I helped my mother set up a home, helped my siblings with their studies, and started volunteering with an NGO. It felt good that I could help people when I was suffering too.”

“As women, living in the camp is not easy. We face more problems than men. Law enforcement and other support systems were not in place at the start. So a female leader was needed back then – someone who can listen to women, understand, and speak on behalf of them.”

Sometimes, there’s not enough water and food…

“In order to use health services, people have to wait in long queues. Often, they are only given paracetamol if they are sick. Those who have enough money can pay for better treatment outside the camp.”

“Food is provided by the World Food Programme, but it is not enough. We are given 20 litres of water per person every day – it takes two litres just to use the toilet. We have to collect water in groups at night or in the morning. We can only fill three or four water jars at a time, which is not enough for a family. There's no other way to collect clean water. There’s a little lake here and the water is very dirty. But sometimes people collect water from there as well when they need more.”

… and tiny tent homes are fragile and cramped.

“The biggest problem living inside the camps is our living space. It’s very small for us, 5-12 people are sharing a house. The houses are made of bamboo wrapped with plastic. We get only 60 bamboo pieces and one piece of plastic per family to build a house. In summer, it gets very hot. In winter, due to fog, the plastic portion catches water and our beds get wet. We don’t have electricity at our camp houses. NGOs provided us with rechargeable lights, but they don't last through the night. People who have enough money and jobs can buy solar panels and batteries.”

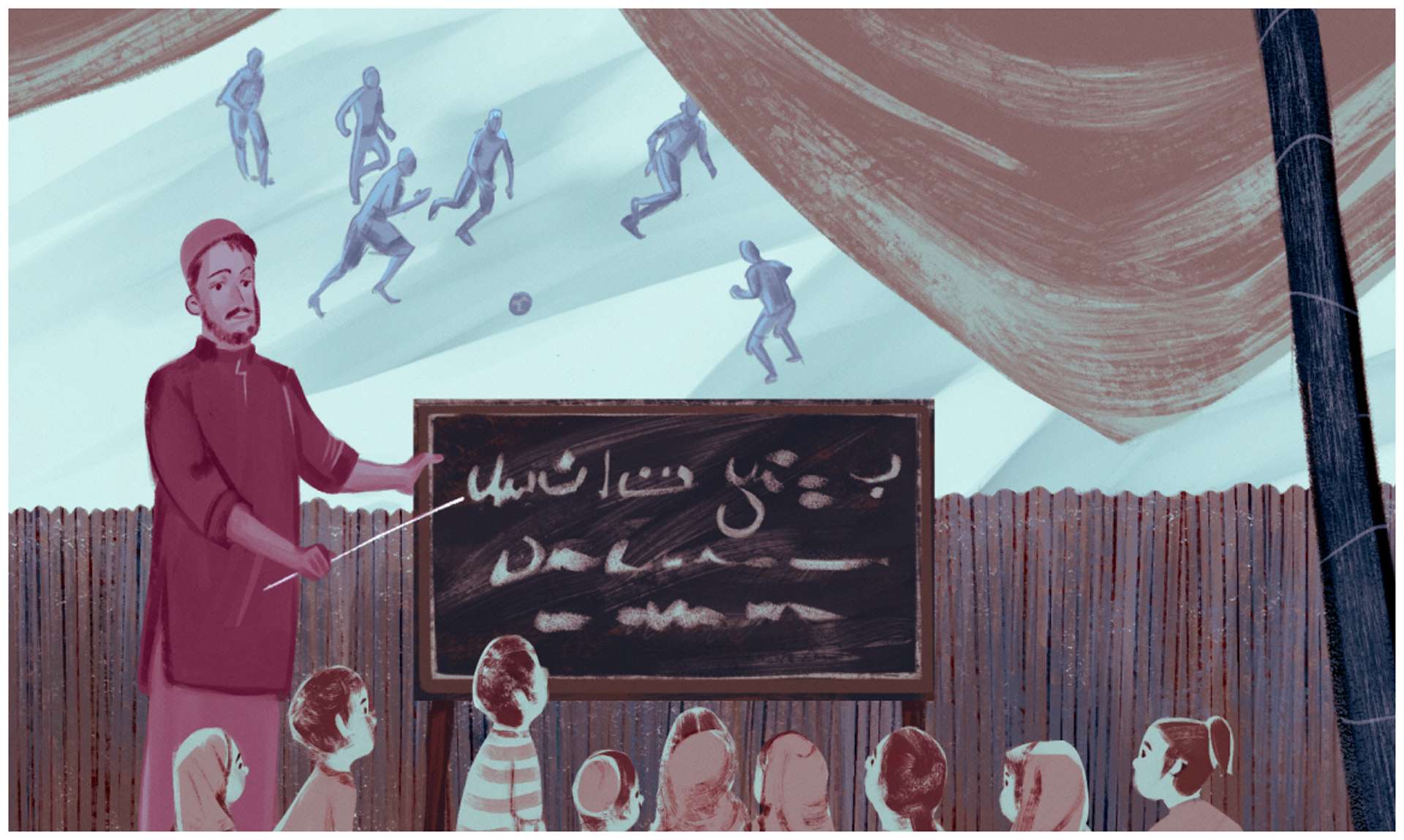

But the biggest worry is the future. There is no formal schooling for most Rohingya, especially teenagers. There are NGO-run classes teaching basic lessons to younger children, but these were shut through most of the COVID-19 pandemic.

“Education is a crying need.”

“There is no education system for young women – only for children under 14. Some women can't even write their names. They can’t read signboards. If we can get an education, I believe we won’t be victims like we are now.”

“There is primary level school, which is good, but what about higher studies after passing the primary level? There’s no scope for high school studies. If you want to make a society strong, education is most important. If there’s no education, people won’t be able to understand the services provided by NGOs.”

Hafsa worries about what will happen to Rohingya children without a proper education. She wants to become a teacher, and to be a voice for the youngest generation.

“To me, the biggest problem for my community is education. If you see the total population of the Rohingya community, most of them are children. My younger siblings are studying back in the camp with the help of a private tutor, who our family pays. But there is no institutional support for higher education. Not everyone is able to spend money for private education, and not everyone has permission from home to attend the NGO schools."

“If there's education for everyone, every other problem will begin to find its solution.”

Women like Romida and Hafsa often clash with their community’s expectations. Rohingya society can be conservative. Women are usually expected to stay home – and not be active in public life. Hafsa wants this to change.

“Because of my education, I see myself as a leader in my community. I believe a woman is a born leader. I see my mother managing a house, which is similar to governmental work: It’s like managing a country. I am a leader of my house, even if society doesn’t accept me as a leader.”

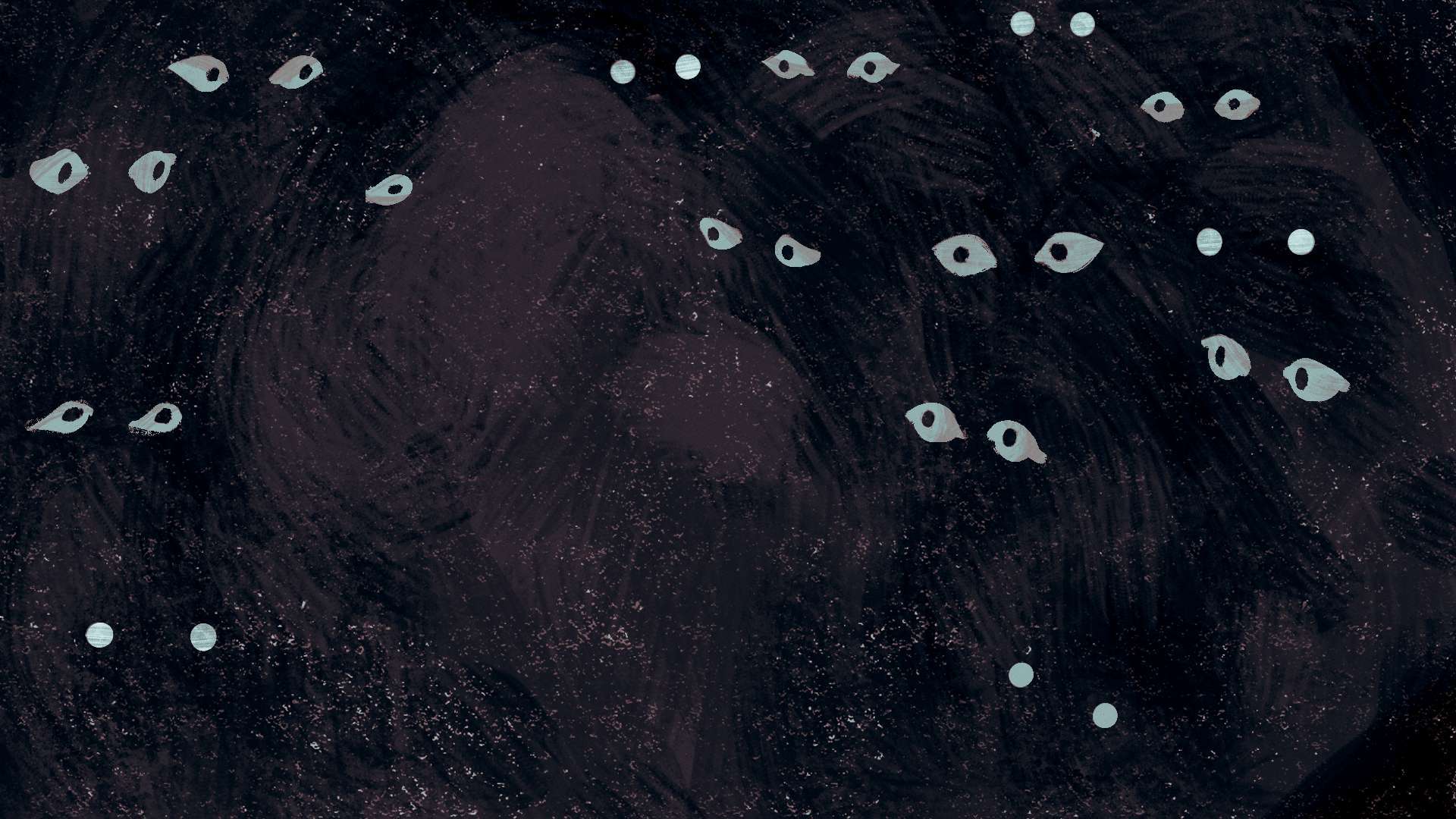

As an outspoken leader, Romida fears she could become a target. Many Rohingya say the camps have grown unsafe – especially at night. Conservative groups in the community are pressuring women not to work or volunteer.

“My future is a bit uncertain. For my own security, I don’t want to participate in elections anymore, so I have decided not to stand in future ones. I feel like I could be threatened.”

The entire community's future is also uncertain. Few Rohingya have ever been resettled from Bangladesh; some have lived here for decades. Rohingya in Myanmar's Rakhine State still face heavy restrictions. Most refugees say it's not safe to return – especially after Myanmar’s military seized power in a coup in February 2021. But Romida and Hafsa say Bangladesh’s refugee camps will never feel like home, either.

“Ultimately, I want to make conditions better for our community, but I don’t see any future in Bangladesh. I am living here like a guest. We had open spaces in Myanmar. When it’s too hot here, I remember how we used to enjoy the breeze, sitting in the yard.”

As long as she remains in Bangladesh, Hafsa wants to help her community.

“There’s no end to learning. I hope to become a social activist who will work for her community. I want to ensure graduation for every Rohingya child out there.”

But her thoughts are still in Myanmar. She remembers how her father used to help her with the housework, even though it was her job, and how he prepared the children’s beds at night before they slept. She dreams of a day when she can safely return home, re-uniting her family.

“Every second, every moment is a memory now.”

“It’s hard to have my father still in Myanmar, but we want him to live there. It makes us feel like we still have a connection with our country, like there’s still a hope to get back home.”

Credits

This story was produced by The New Humanitarian and PositiveNegatives

Research: Sabiha FaizIllustration: Fahmida AzimProduction: Sara Wong and Irwin LoyLogistical support: Shafi MohammedAdditional video: Rajib MohajanSatellite imagery: ESAMusic: Axletree, Chris Zabriskie, Podington Bear, Blue Dot SessionsAdditional translations: NaTakallam