2011

Syrians begin to flee their homes.

Protests against the government of Bashar al-Assad are met with deadly violence, and unrest spreads across the country as members of the opposition take up arms.

People begin to flee their homes in the thousands, taking refuge in safer parts of the country, or abroad: Turkey opens its first camps for Syrian refugees, who are able to cross back and forth between the two countries with relative ease.

2012

729,000 Syrians are refugees.

2 million are internally displaced.

195 Syrians are resettled in third countries.

The Syrians who flee their homes mostly take shelter with friends, relatives, and even welcoming strangers across the border. But as the numbers increase and the UN’s refugee agency, UNHCR, scales up its capacity to register new arrivals, Jordan opens its first official camp for Syrian refugees, Za’atari.

After just one year, Za’atari is already home to 120,000 people, and new arrivals are still streaming in. Our correspondent reports a night she spent in the camp: “Many [refugees] have spent days en route, trying to escape Syria. They include pregnant women and sick children. At the border, they are met by Jordanian soldiers, who board them onto buses to the camp. I watch as they unload their suitcases, some of them clearly exhausted.”

2013

2.5 million Syrians are refugees.

6.5 million are internally displaced.

607 Syrians are resettled in third countries.

In March 2013, Syria’s war passes the grim landmark of having produced one million refugees, including 400,000 who fled escalating violence in major cities like Aleppo and Damascus in the first three months of the year alone. Around half the refugees are children. Most are staying in Lebanon, Jordan, Turkey, Iraq, and Egypt. Germany begins a “humanitarian admissions” programme – which grants residency and some rights, but not citizenship, to 20,000 Syrians by 2015.

In a five-part diary, an anonymous writer tells of his decision to flee Damascus, life in exile in neighbouring Lebanon, opting to return home, and the horror of trying to contact friends while bombs rained down and a chemical attack hit not far away, in Douma. “I tried contacting friends living in the targeted towns,” he writes. “The cellular network was down, as it often is. On such nights, it’s normal to lose a friend or two. I was worried about each and every one of them. Unlike the news outlets, which tally casualty numbers, for us, these numbers are memories, parts of life and cells of the heart. I only managed to reach two of them within the next three days; I don’t know the fate of the others.”

2014

3.9 million Syrians are refugees.

7.6 million are internally displaced.

6,367 Syrians are resettled in third countries.

The so-called Islamic State announces its self-proclaimed caliphate over parts of Iraq and Syria in 2014, and declares the Syrian city of Raqqa its capital. A US-led coalition begins airstrikes against the group the same year. More than 76,000 people die in 2014, according to one conflict monitor, bringing the death toll of Syria’s war to over 200,000.

The number of registered Syrian refugees in Lebanon reaches one million. The Lebanese government does not allow official camps, so many refugees live in host cities or towns and informal “refugee settlements”. In 2015, when their numbers reach around 1.5 million, the government stops allowing the registration of refugees.

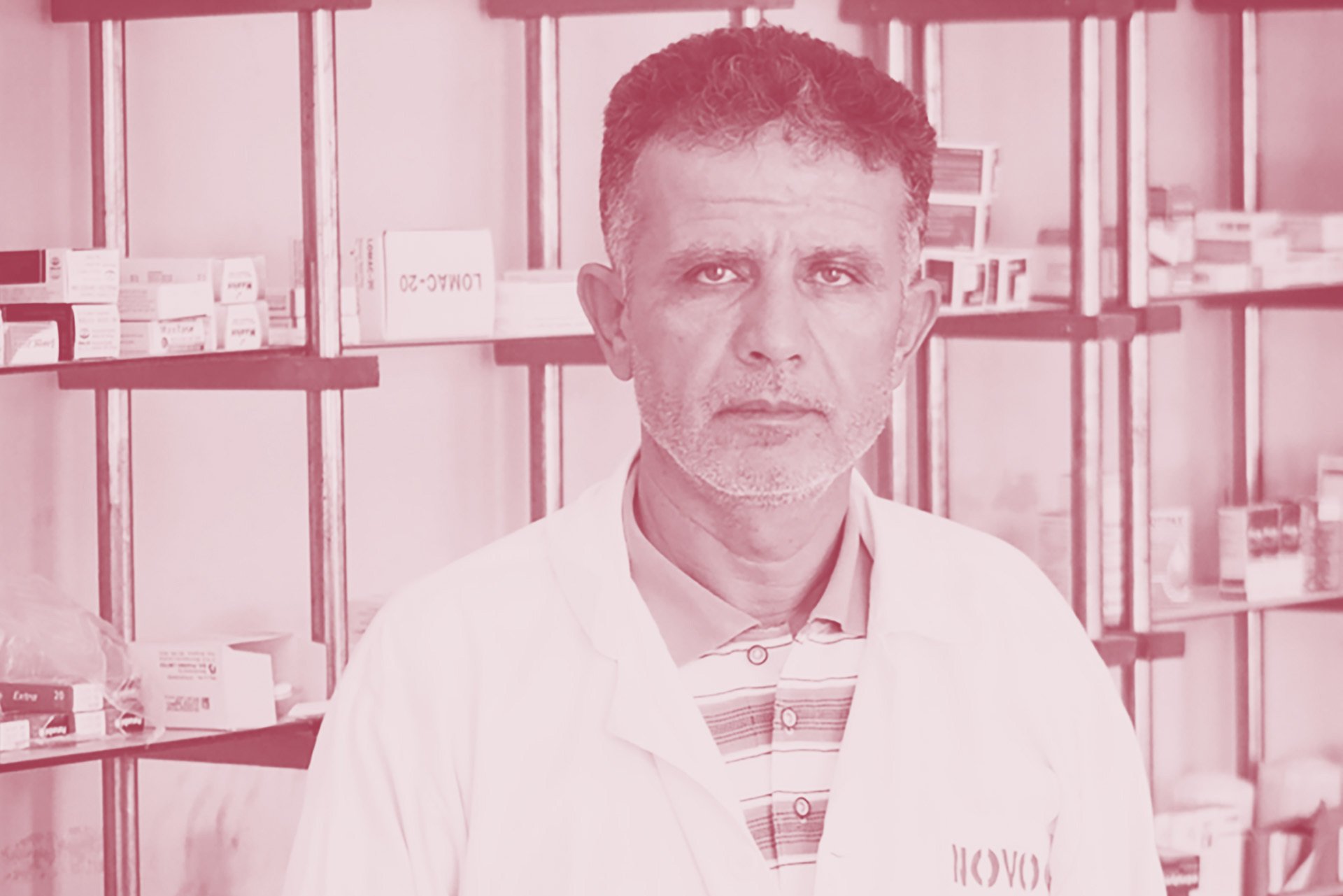

The vast majority of Syrian refugees are in debt and struggle to get by on the limited aid they receive. Samira, originally from Idlib, explains how her seven-person family tries to make do with $105 in monthly aid and an additional monthly income of $250: “Everyone in the family has high blood pressure, and we need medicine all the time. But it's not covered by the UN, and I’ve tried to find organisations that can help us, but I don’t know where to go. I have a $3,000 debt with the pharmacist. It’s a terrible feeling: The feeling you owe someone for something so important for your survival.”

2015

4.9 million Syrians are refugees.

6.6 million are internally displaced.

17,717 Syrians are resettled in third countries.

Many Syrian refugees initially fled to places like Lebanon, Jordan, and Turkey, but with the longer-term hope of starting over in safe countries further afield, often via the UN’s resettlement programme. But the wait for resettlement is long, and only a fraction of families put forward by a UN screening process win a place. As the system often results in disappointment, many refugees try alternative, often deadly, routes. Some even fly to Mauritaniaand attempt to cross the Sahel for the chance to reach Europe. In 2015, more than a million people – five times the number the previous year – arrive in Italy and Greece by boat. Most are Syrians. Several European countries put up fencesto prevent migrants, including Syrians, from entering.

3,771 people die while trying to cross the Mediterranean, including three-year-old Alan Kurdi, who drowns with his mother and his brother when their smuggler’s boat capsizes. The image of his body, washed up on a Turkish beach, came to represent what became known as the “refugee crisis”. But refugees are much more than objects of pity. On the Greek island of Lesvos, newly arrived Syrian doctors, football coaches, hairdressers, computer scientists, and lawyers speak of their career ambitions, and what they have to offer Europe.

2016

5.5 million Syrians are refugees.

6.3 million are internally displaced.

65,843 Syrians are resettled in third countries.

Syria’s war drags on, and a long and brutal campaign forces the last rebels out of Aleppo by the end of 2016. This year, a UN officialputs the death toll at around 400,000. But the number is still based on old figures. It was so hard to keep an accurate tollthat the UN’s official death count was stopped in 2014.

Meanwhile, the options for peopletrying to flee the country are dwindling. Jordan, Lebanon, and Syria have all instituted policies that tightly control new entries. In March, the EU signs a controversial dealwith Turkey to stem the flow of migrants into Europe. By October, some 70,000 people are stuck in the deserton the border with Jordan in desperate conditions, unable to cross into Jordan and unwilling to return to danger. Some remain there to this day.

While their immediate neighbours have become less welcoming, some Syrians have managed to take advantage of open-door policies further afield, ending up in some unexpected places, including...

... Mauritania...

... Sudan...

... and Brazil.

Some 172,000 refugees, including 65,000 Syrians, are resettled worldwide in 2016, the largest number since 1990. This includes people going to Canada, which since the 1970s has allowed groups of people to sponsor the resettlement of individual refugees or families. In addition to making a financial commitment, sponsors provide practical and emotional support as the new arrivals ease into their homes. This private sponsorship programme takes off in 2016. Iman, Zaher, and their two daughters arrive in Ottawa via Toronto and Beirut, not speaking a word of English, greeted by the 38 Canadians who banded together to sponsor their trip.

2017

6.3 million Syrians are refugees.

6.2 million are internally displaced.

40,192 Syrians are resettled in third countries.

Following the 2016 EU-Turkey deal, informal migration to Europe drops sharply as high-tech security fences are erected along the Bulgarian-Turkish border, and increased naval patrols monitor the Aegean Sea. To avoid these obstacles, smugglers begin taking people on boats from Turkey to Romania, plying the rough Black Sea waters.

Most people who arrive in Romania hope to seek asylum elsewhere, but some are returned to the country by the “Dublin Regulation”, which gives member states the right to return asylum seekers to their first country of arrival in the EU. This happens across Europe. For example, Anas, a 27-year-old Syrian who escaped besieged Eastern Ghouta, took a smuggler’s boat from Libya to Lampedusa, and then eventually made it to Sweden and then Germany before being arrested and deported back to Italy – this was despite having a letter from a doctor saying his medical state was so severe he should remain in Germany for treatment.

Back in Italy, Anas was fingerprinted by police, and handed some paperwork. “I asked them where I should go. I was bleeding. Really, there was blood everywhere on my pants… They said, ‘Go sleep in the street’. I didn’t have any money. I couldn’t sleep in a hotel. Where was I supposed to sleep?”

2018

6.7 million Syrians are refugees.

6.2 million are internally displaced.

34,126 Syrians are resettled in third countries.

Despite a new pact, and promisesto take in more refugees from around the globe, refugee resettlement drops off, hitting a 10-year low in 2018. The drop is mainly due to President Donald Trump’s decision to slashrefugee admissions to the United States.

At the beginning of the year, hundreds of thousands of peopleare trapped in the rebel enclave of Eastern Ghouta, running desperately low on food and medical supplies as they are besieged and bombed by government forces. The siege ends in April as rebels are evacuated. In the same month, the Palestinian refugee camp of Yarmouk – besieged for years and now controlled by IS – is hit with airstrikes, forcing thousands of civilians to flee. Some of the Palestinians join Syrian refugees in neighbouring countries, especially Lebanon. “The situation facing Palestine refugees in and around Yarmouk is unimaginable,” says a spokesperson for the UN’s Palestine refugee agency, UNRWA. “In Yarmouk itself, thousands of homes have been destroyed and the last remaining hospital [has] been rendered inoperable by fighting. We call on all sides to spare civilian life and infrastructure. The situation they face is piteous.”

2019

6.6 million Syrians are refugees.

6.1 million are internally displaced.

30,686 Syrians are resettled in third countries.

Governments and politicians in Lebanonand Turkeyenforce increasingly harsh restrictionson Syrians, as public callsgrow for refugees to return. Some people find refugee life so hard they decide to take their chances and go back to Syria. Meanwhile, conditions at the Moria reception centreon the Greek island of Lesvos deteriorate, as 12,000 people – more than four times the number it was designed for – shelter there. People are packed into shipping containers or makeshift tents, and allegations of rape are common.

Inside Syria, smugglers report a growing demand for their services as a Russian-backed offensive by al-Assad’s forces in rebel-held Idlib leads to a drastic increase in violence. Scrambling to get into Turkey, people like Omar Mubarak are selling their belongings and risking the potential of being shot or turned back at the border, often trying multiple times. “I’m living in a state of constant anxiety,” says Mubarak of his failed attempts to cross with his wife. “Despite all this tragedy and danger, even this is better than staying under the bombs.”

2020

6.6 million Syrians are refugees.

6.7 million are internally displaced.

9,377 Syrians are resettled in third countries.

UNHCR says 2020 marks the lowest number of refugee resettlementsby the UN in two decades, partly due to the pandemic. By the end of the year, 9,377 Syrians are resettled – in Canada, Germany, Sweden, and 17 other countries.

Over the course of the government offensive to retake Idlib, hospitalsand, by the time a ceasefire is announced in March nearly a million people have been forced to take flight in and around the province in just a few months. For many, this is not their first displacement in Syria’s long war. Having taken shelter in makeshift camps, people who have escaped one deadly front line are now faced with a new threat: COVID-19. Nisreen al-Mahmoud, who fled bombardment in her hometown, is living in a tent with her son. “I can’t sleep at night anymore. My mind is occupied with how I’m going to protect myself and stay away from other people during this period, since I heard that we shouldn’t mix with others,” she says. “I’m afraid of dying, and I hope it’s not from this illness.”

2021

6.6 million Syrians are refugees.

6.7 million are internally displaced.

The new US administration pledges to allow 125,000 refugeesinto the United States per year, in contrast to the 12,000 (including only 365 Syrians) admitted in 2020. President Joe Biden’s plan mentions refugees from Syria, where it says “regime forces have forcibly displaced, raped, starved, and massacred civilians.” A private sponsorship scheme similar to Canada’s will also be piloted.

After 10 years of war, the vast majority of Syrians who fled horrific violence, abuse, and repression remain relatively close to home, either in the region or inside the country. A lucky few are in the queue for a new beginning in a new country. But most are in limbo, unable to build a new life where they are, and often unwilling to go back to the dangers they know – and the risks they fear – in a homeland in ruins.