Joshua Collins

Freelance journalist, based in Bogotá, focused on migration and violence

DARIÉN GAP, Colombia

Migrants and asylum seekers are being apprehended in record numbers at the southern US border, where a new surge is expected from later this month as COVID-related restrictions are lifted. They come from Mexico and Central America, but also from the Caribbean and South America, even from Africa and the Middle East, escaping disasters, poverty, and repression. In the countries they transit through, they’re often viewed by authorities as numbers to register, problems to control, even to expel. For most, the goal is to reach the US to build new lives. In spite of the dangers and endless bureaucratic and legal hurdles, some do succeed. All experience suffering and fear along the way. This is the journey of one of them.

Will* is an asylum seeker from Cuba, where rising poverty and discontent sparked rare mass street protests last year followed by an immediate government crackdown. Food, medicine, and fuel shortages – worsened by the pandemic, the war in Ukraine, and US sanctions – have seen record numbers of Cubans taken into custody at the US-Mexico border: Cubans are second now only to Mexicans in terms of monthly apprehensions, ahead of Guatemalans and Hondurans.

After relocating to Venezuela in 2017 on the orders of Havana, Will took the decision to leave the country in 2021 after the Venezuelan government told him he risked being deported back to Cuba due to his opposition to the socialist Maduro regime that holds power in Caracas.

To reach the United States, Will faced a journey of 6,000 kilometres overland from Venezuela. He would have to navigate some of the most dangerous migration routes in the world: the Darién Gap, a jungle corridor between Panama and Colombia controlled by armed groups and smugglers; Central America, where migrants are routinely preyed upon; and southern Mexico, where a whole new set of risks awaited.

“Migrants face incredible dangers,” William Spindler, the Panama-based regional spokesperson for the UN’s refugee agency, UNHCR, told The New Humanitarian. “We see people robbed multiple times throughout the journey. People disappear. Women often face sexual assault. Some are detained by authorities in the countries they pass through.”

Through face-to-face and phone interviews, as well as regular updates via WhatsApp, The New Humanitarian pieced together the route Will took and explored the challenges he faced – and which tens of thousands of people like himcontinue to face every month.

Migrants known to have survived passage through the Darién Gap, 2021

Monthly apprehensions at US-Mexico border

| J | F | M | A | M | J | J | A | S | O | N | D | |

| 2020 | ||||||||||||

| 2021 | ||||||||||||

| 2022 |

It was in Acandí, a small but bustling jungle town near the southeastern entrance to the Darién Gap, that we first encountered 40-something-year-old Will in late August 2021. Like other migrants, he had arrived there on a small boat from Necoclí, a town across the Gulf of Urabá that’s reachable by road from the rest of the country. In Acandí, hordes of vendors peddled overpriced goods for the trek ahead, while a folksy Colombian country music called vallenato blared endlessly from the hut where “security guards” belonging to a local armed group oversaw the murky business of human smuggling.

Sitting on a log near a tent he had brought for the trip, the silver-haired migrant – who asked that his last name be withheld – reviewed the survival equipment he had gathered for the arduous hike ahead. As he continued his preparations, hundreds more migrants mulled around nearby, many of them clearly worried about the next stage of their journey. Informal “guides” hawked their services, haggling with the small groups they were offering to lead for five to eight days through the dense jungle, which is controlled by armed criminal groupson both sides of the Colombia-Panama border.

At the time Will was in Acandí, the Colombian authorities said they had never seen so many people passingthrough the hostile region. Numbers have soared even higher in the eight months since.

Surviving the Darién Gap

Keep scrolling down to follow Will’s journey.

Those seeking to cross the Darién Gap must first reach Necoclí, a migration hub on the eastern side of the Gulf of Urabá, before crossing via a small ferry to Acandí. An agreement between Colombia and Panama in August 2021 to cap the number of migrants crossing the gulf daily to 500 was quickly overwhelmed. Demand was much higher, with up to 20,000 migrants amassing in Necoclí by late September. Some try their luck with smugglers and attempt clandestine sea crossings, resulting at times in deadly shipwrecks.

On arrival in Acandí, migrants hire informal guides. After being matched up, the guides wake everyone the following day at 3:45am for a pre-dawn departure.

Within 10 minutes, migrants find themselves waist-deep in a river, their clothes and footwear already sodden. Walking upstream is slow, the uneven stones taking a toll on travellers' ankles. Many embark on the journey in flip flops, Crocs, or now-ruined Nikes. Often, they end up in shin-deep mud, pulling a foot out only to find the shoe gone. Some recover their buried shoes. Others don’t and have to continue in their socks or barefoot.

A few hours into Will’s journey, a woman faints. She is in no physical condition for this trip, but she has no choice. The alternative is to remain in Colombia without her family. Her fellow travellers help her up, but she is soon reduced to crawling on her hands and knees through the mud. They encourage her to continue, even though they have no real idea how much farther they have to go.

Between Acandí and Bajo Chiquito on the Panamanian side, migrants are at the mercy of armed and criminal groups. “I hear criminals are robbing people of everything they have,” says Yordany Herrera, a Cuban who travelled by land from Peru to the Darién Gap and is headed to the United States. “I’m not worried. I will stop to work along the way if I need to. I’ve been a chef, a construction worker, a waiter, a carpenter. I can do anything.”

← Will at his tent, somewhere on the Colombian side of the Darién Gap, late August 2021.

Two days after departing Acandí, migrants arrive at the Panamanian border. It’s the end of the road for the Colombian guides, as the Panamanian side is controlled by different armed groups. For many migrants, it’s confusing and disappointing to discover they are still less than half way through the Darién Gap: another two to five days of travel remain, depending on their pace.

Finally, the migrants who have survived the journey arrive in the small Indigenous community of Bajo Chiquito, where new arrivals are registered before being transported along the Turquesa river to a migrant reception centre in the small town of Lajas Blancas.

Six days after we said goodbye to him in Acandí, The New Humanitarian received a phone call from Will. He had made it through to the Panamanian side of the Darién Gap. “I wouldn’t recommend that journey to anyone,” he said. “It’s dangerous. There isn’t clean water. The terrain is brutal. We saw dead bodies. No matter how much you want to get to Mexico or the US, it isn’t worth the risk to cross that jungle.

Asked months later how many corpses he had seen, Will responded: "I counted around 49. There could have been more. There were many bodies that you couldn't see, but when you passed you could smell the odour and know that there was a dead person there."

Aid groups operating in the region said migrants often end up dead or missing in the Darién Gap, which can only be crossed on foot. On the Panamanian side, robberies and assaults by the local criminals who control the trail are commonplace.

“We are treating victims of sexual assault, wounds resulting from attacks, pregnancy complications, families arriving incomplete,” said Santiago Valenzuela of Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF). The organisation operates an outpost in Bajo Chiquito, a small Indigenous community as you emerge from the jungle on the Panamanian side.

Last year alone, MSF provided medical treatment to over 40,000 migrants at Bajo Chiquito, and further downriver in the small town of Lajas Blancas.

“We treated one woman who was trapped in the jungle for three months due to a broken ankle. She was suffering from malnutrition and acute dehydration as well as secondary infections,” Valenzuela recalled. “Some people have been robbed three or four times. They emerge with nothing.”

In 2021, Panamanian officials recovered 50 bodies from the Darién Gap, more than double the 2020 figure. They believe that’s only a small portion of those who succumbed during the trek, as most deaths go unreported and their remains are never retrieved.

The Panamanian government said more than 130,000 migrantsentered the country from Colombia in 2021. Nearly 80,000 were Haitians, but many also came from Cuba and Venezuela, and from a range of West African countries.

UNHCR, MSF, the International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies (IFRC), and the International Organization for Migration (IOM) all work with the Panamanian government to provide medical care and temporary shelter to thousands waiting in small communities near the Colombian border.

There’s limited capacity at the migrant reception centre in Bajo Chiquito. On arrival in Panama, most migrants are placed in a processing camp in Lajas Blancas, where they often have to wait for weeks to continue north. Since the pandemic, migrants have also had to spend two weeks in quarantine to prevent the spread of COVID-19.

Will said he arrived in Panama “destroyed, wasted, and bloodied”, before spending two weeks in the government-run centre in Bajo Chiquito. He was then allowed to continue northwards by boat, before being transported discretely and efficientlyto Panama’s border with Costa Rica. “They put you on a bus,” he said. “They don't want you to have any contact with Panama. They pick you up in Lajas Blancas and drop you off at the border. The whole trip is at night so that there’s absolutely no contact with people."

Staying hidden through Central America

From Panama, migrants and asylum seekers disperse into smaller groups as they head through Central America and into Mexico, often crossing borders irregularly and on smugglers’ trails to avoid detection, detention, and deportation by the authorities.

Existing outside of any government databases – the Panamanian government registers those it finds arriving from the Darién Gap – they become less visible to officials, as well as to any aid groups collecting data.

“The migration is irregular and very difficult to track,” said Spindler, the UNHCR spokesperson. “They cross most of the continent as invisibles. We only see them at concentration points where they are forced to wait, like Necoclí or southern Mexico.

“We’re talking about the main migration route in the Americas,” he continued. “It is one of the most dangerous migration routes in the world, but we only hear about it at bottlenecks or when tragedies happen.”

The exceptions are the occasional caravans– large groups – of Hondurans and Guatemalans who congregate in their thousands and travel together for safety, only to often be turned away at borders and/or broken up as crackdowns ensue.

Although most Central American countries don’t deport migrants, bureaucratic obstacles are increasing, including in Mexico, where visa requirements for certain nationalities have been toughened and deportations are also on the rise. Nicaragua, which earlier in the pandemic was making its own citizens pay for expensive COVID-19 tests to return to the country – has begun charging migrants $150, the same magic number – to transit through.

Will went more silent as he made his way through Central America, checking in less frequently. He said he felt lucky to have made it through the Darién Gap without serious incident. But on crossing the border into Costa Rica, he was robbed for his cellphone and the cash he carried. He then had to work informally for several weeks to raise enough money to cross Nicaragua.

Keep scrolling down to follow Will’s journey.

From Bajo Chiquito, migrants begin long journeys through Central America beset by obstacles ranging from extortion to unexpected border-crossing fees.

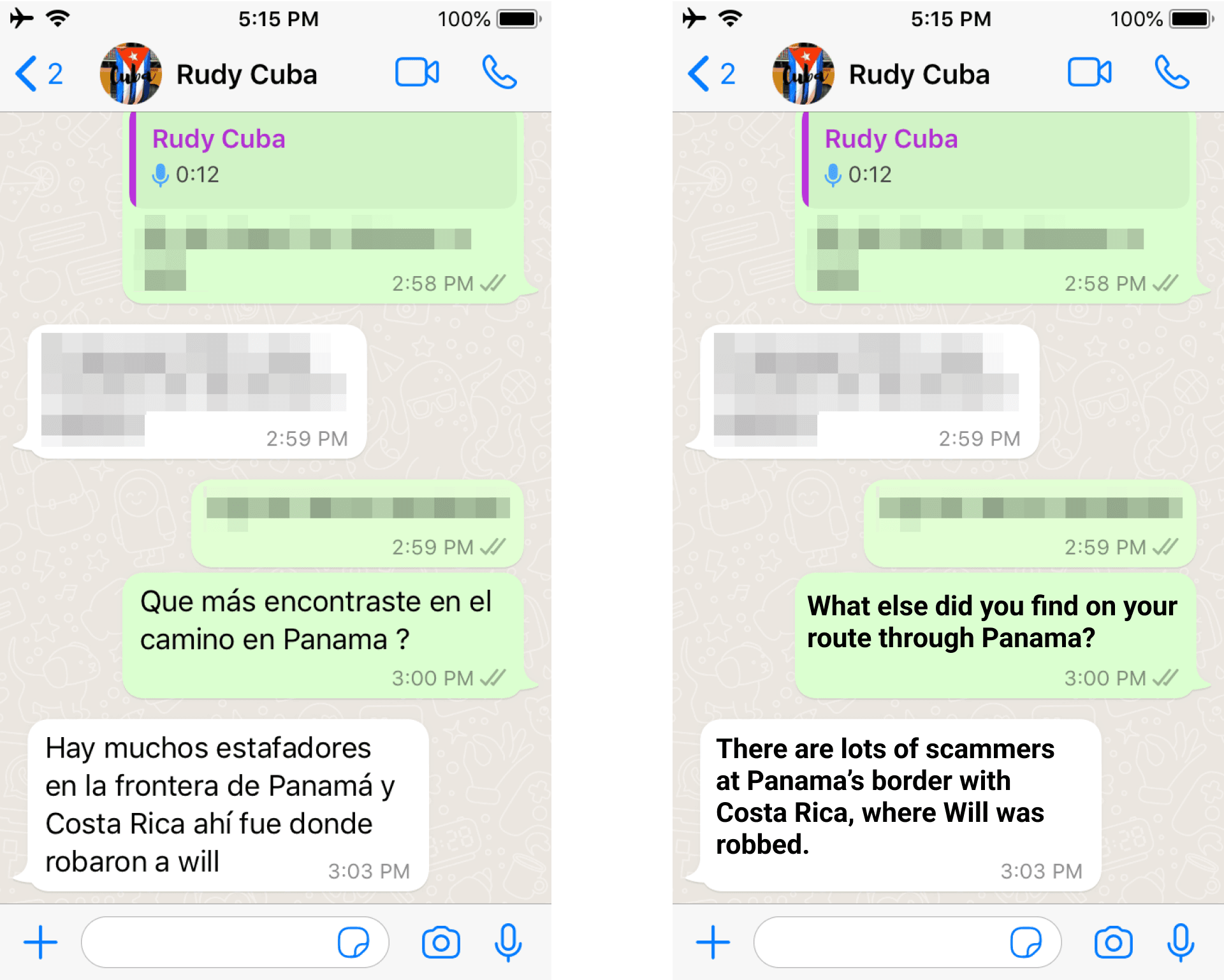

Text message from Rudy, Will's travel companion, to The New Humanitarian (original message on the left, English translation on the right)

Text message from Will, sent on 6 October 2021 from Costa Rica’s border with Nicaragua (the photo opposite is an archive photo of the same border crossing taken in 2015).

← Migrants crossing Honduras, where thousands more people join the journey northwards, fleeing violence, poverty, climate disasters, and in search of a better life.

At Guatemala’s frontier with Mexico, Will finds relatively easy passage. There are no guards patrolling the river border, which he crosses for a small fee.

Women are particularly vulnerable during this part of the journey.

In a 2021 report by the Wilson Center: “Of the 25 most dangerous places in the world for women, 10 are in the Western Hemisphere, with Central American countries Honduras and El Salvador near the top of the list, at numbers two and four respectively.” Migrant women are even more vulnerable than citizens of the region.

According to MSF, 68 percent of migrants and asylum seekers interviewed along the Central American migration route are exposed to violence, and nearly one third of women surveyed had been sexually abused. It has described the high levels of violence in the region as comparable to those in the war zones it operates in.

At this stage of the route, joining those like Will who arrived through the Darién Gap from South America, or who have flown directly into the region from the Caribbean or elsewhere, are thousands of migrants from Central America’s Northern Triangle countries: Honduras, El Salvador, and Guatemala. Record numbers of Central Americans, often escaping crime or natural disasters as well as poverty, headed northward in 2021.

To stay in Mexico or go on?

Migrants queuing in May 2021 for dinner at the Jesús El Buen Pastor shelter in Tapachula, Mexico, where they are forced to wait for months before being allowed to proceed northwards. (Jordan Stern/TNH)

When migrants and asylum seekers reach Mexico, they have to announce themselves to authorities or risk being detained or deported. The migrant population once again becomes visible in large numbers, especially in small border towns in some of the country's poorest states.

Arrival here may mean waiting for months for documentation – both for refugee status within Mexico and permissionto head to the US border – before being allowed to continue northward. In the interim, employment opportunities are virtually nil.

Tapachula, where many migrants and asylum seekers find themselves legally stranded, is blisteringly hot. During the day, thousands wait endlessly in the shade, clutching identical translucent plastic envelopes stuffed with application papers or wearing their passports around their necks. Most possessions can be replaced, but the immigration papers contained in those envelopes are priceless and never leave their side.

None of the new arrivals want to be in Tapachula, but the town has become the de facto holding ground for migrants from Central America and beyond. Those attempting to leave the region while their cases are being reviewed may end up at Siglo XXI, Latin America’s biggest migrant detention centre, notorious for overcrowding and allegations of detainee abuse.

In 2021, Mexico detained over a quarter of a million migrants, the majority in Tapachula. According to the law, migration cases for detained foreigners should be resolved in 15 working days, but that provision was extended to 90 due to the backlog, and some migrants report waiting even longer.

As a result, many give up plans to continue north and decide to apply for asylum in Mexico. Asylum claims in Mexico reached an all-time high in 2021 of over 130,000. Detentions and deportations of migrants also skyrocketed, according to government statistics.

Mexico’s southern border states of Chiapas and Tabasco have been unable to cope with the soaring number of asylum applicants, most of whom stay in the border cities, explained Adam Isacson, of the Washington Office on Latin America (WOLA). “COMAR (the Mexican migration service) doesn’t have the resources or the personnel to handle this,” Isacson said. “They are overwhelmed.”

UNHCR has programmesdesigned to help those who decide to stay in Mexico regularise their migration status, find work, and obtain housing, but it’s a process that takes time, and the agency’s workers in southern Mexico are unable to assist everyone.

Spindler said the organisation had requested more resources from both the US and the UN to deal with the increased demandin the region – not only to assist the increased numbers of migrants heading northwards, but also deportees sent back by the US.

After being robbed in Costa Rica and narrowly escaping detention in Nicaragua – he only avoided it by bribing a border guard – Will eventually managed to cross into Mexico from Guatemala, where he made contact once again.

Although Will did manage to avoid Siglo XXI – a slice of good fortune other migrants in touch with The New Humanitarian did not share – he was still left languishing for weeks, awaiting Mexico's labyrinthine bureaucracy, like virtually all his fellow travellers.

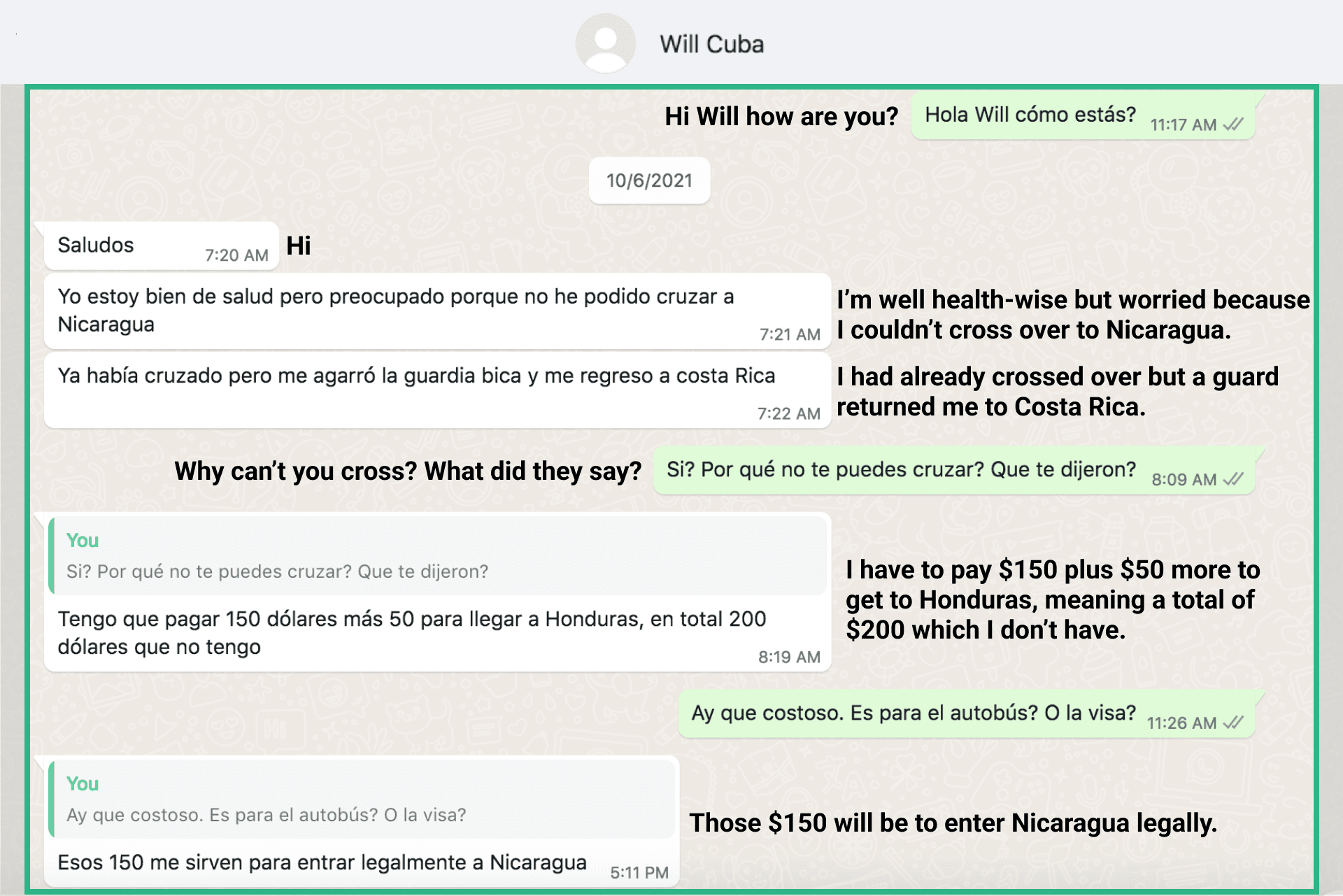

“I am opting to apply for the humanitarian visa, but they told me that I cannot leave the state with the humanitarian visa,” Will messaged from Palenque, in northern Chiapas. “It doesn’t matter. If they give it to me, I will take off and go from here to there.”

While cases are reviewed, migrants are prohibited from leaving the department in which they filed their claim.

Ongoing protests by migrants in southern Mexico demanding the right to work and continue north have further strained difficult relations with local residents, leading to a rise in anti-immigrant sentiment.

Locals often complain about increasing crime rates, being “overrun” by migrants, and how Tapachula has changed for the worse.

Graver risks from drug and criminal gangs are also ever-present.

“There is no work here,” Will said from Palenque. “Just gangs, organised crime, hunger, and xenophobia.”

One of Will’s travel companions was kidnapped shortly after his arrival in Mexico. For three days, he heard nothing and assumed he had been killed. Will then learned that the kidnappers had in fact released his companion after securing money from the man’s relative in the United States.

To the US border

After making it through the Darién Gap and overcoming the legal and bureaucratic hurdles of Central America and southern Mexico, you might think the worst part of the journey to the United States is over. But Will’s updates underlined that this is far from being the case: Mexico is also an extremely dangerous place to be a migrant.

Fear among those about to embark on the journey from southern Mexico is palpable. In Tapachula, no one wants to give their last name, talk about where they are going, where they are from, or if they have family or friends in the United States.

They fear kidnapping, extortion, and robbery from criminals, as well as detention and deportation from the state. And the well-travelled migrant corridor to the United States is also lucrative territory for Mexico’s notorious drug cartels, who battle between each other for its control. Those on the move are also distrustful of Mexican police, who have been involved in multiple killings of migrants; as have the Mexican National Guard, most recently in November, when they opened fire on a bus transporting migrants, killing one and wounding 19.

An accidentin October in Chiapas of a speeding truck illegally transporting migrants that left at least 54 dead drew attention to another risk. The Mexican government has repeatedly vowed to crack down on smuggling groups and cartels who profit from the routes to the US, but little to no progress appears to have been made.

Keep scrolling down to follow Will’s journey.

← Mexican migration officials distribute information to migrants before they leave Tapachula. Here, the guidance they are being given is warning them about the dangers of crossing railway tracks or fast-flowing rivers when they head north. (Jordan Stern/TNH)

Text message from Will, sent on 8 December 2021 from Palenque, Mexico

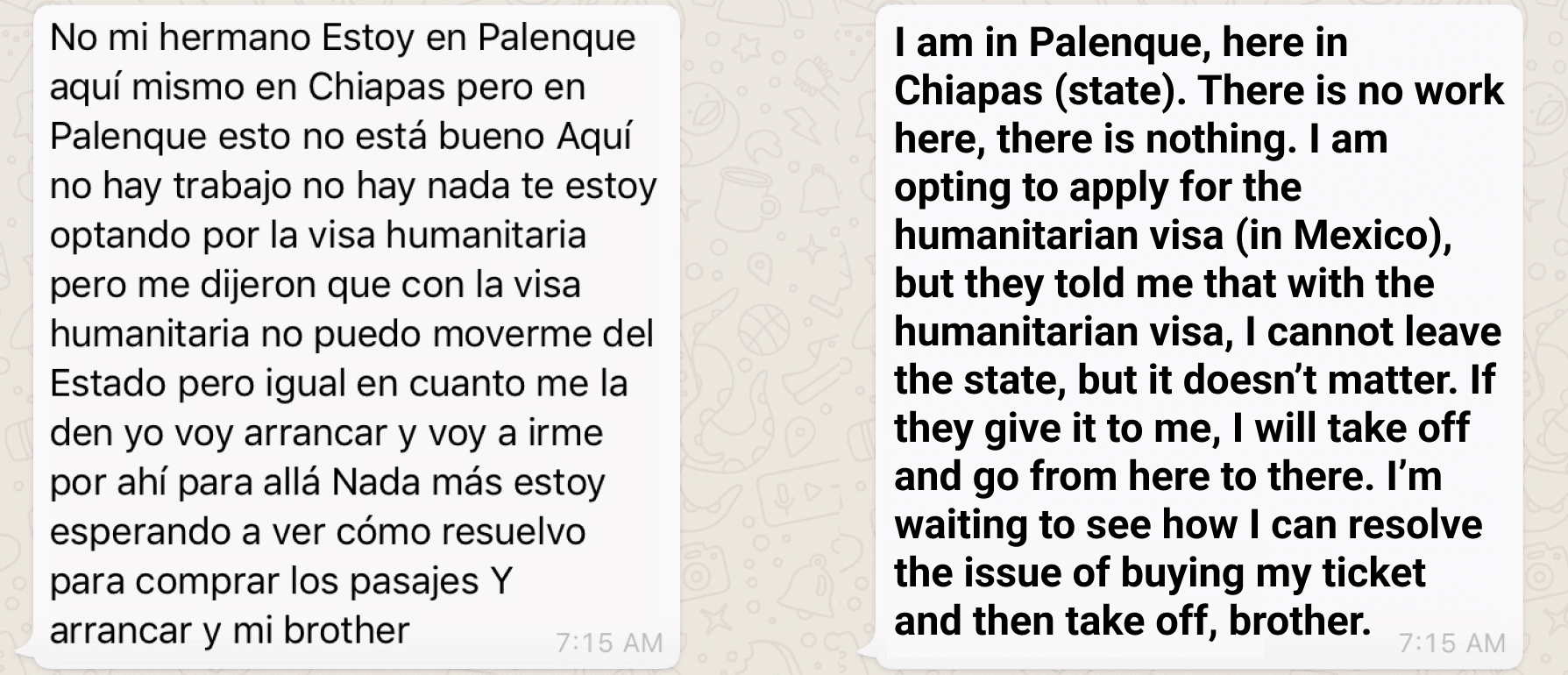

Text message from Will, sent on 11 December from the road between Palenque and Villahermosa

Will sends us three video clips as he struggles to find safe passage through Mexico due to xenophobia and the extreme level of danger he faces from gangs and criminal elements, describing migrants as being “in the eye of the hurricane”.

Finally, four months after we first encountered him in Acandí, we receive this clip from Will “safe and sound” in the United States.

President Andrés Manuel Obrador López has acknowledgedthat Mexico’s strategy of simply trying to contain migrants in southern Mexico is “not enough”, and has called on the United States to increase its assistance. In recent months, the Mexican government has been granting temporary humanitarian work visas to some of those strandedin Tapachula, allowing more of them to head north.

But even after migrants do manage to make their way to northern Mexico, many don’t fare much better. Policies introduced under Donald Trump and continued by President Joe Biden’s administration, including the Migrant Protection Protocols (MPP) and the pandemic-related Title 42, have forced them to wait in overwhelmed townsand facilities where they are vulnerable again to extortion and violence from the cartels and criminal gangs. A recent announcement about the lifting of Title 42, from 23 May, is expected to draw even more migrants to the border, and it is uncertain how the Mexican authorities will cope with the new influx.

Due to the backlog in the US asylum system, the stringent conditions to qualify, and the lack of alternatives for economic migrants, many resort to trying to cross the US border irregularly, risking death in the desert, or apprehension and deportation.

“Without legal avenues for migration, migration will happen illegally, which means people’s lives are at risk as they resort to criminal structures,” explained Spindler, the UNHCR spokesperson.

Since 2021, however, one nationality largely spared from expulsionfrom the US has been Cubans. Unlike Haitians and Central Americans, many of whom are returned to their home countries, single Cuban adults are able to stay while they apply for asylum.

Luckily for Will, this allowed him to complete his journey more easily than compatriots who attempted the trip prior to 2021. “I am now here in the United States. I arrived safe and sound,” Will finally messaged The New Humanitarian from Houston, Texas, four months after we first met him in Acandí.

After crossing the border informally into the United States in late December, Will handed himself in to migration authorities. Still awaiting the completion of his asylum process, he offered few details about the final leg of his journey – he explained that he was working and too busy to answer our questions.

Out of four migrants who remained in sporadic contact with The New Humanitarian for their journeys northward from Acandí – the other three were Haitians – Will was the only one who confirmed US entry without being deported or detained.

Some broke off contact due to lost phones, legal issues, or simple distraction, some were detained by migration authorities. Others perhaps encountered more serious problems that went uncommunicated. Like millions before them, they are the latest “invisibles”.

*Will repeatedly declined to answer when pressed to confirm if Will was his real first name.

Additional reporting provided by Jordan Stern from Acandí, Colombia; the Darién Gap; and Tapachula, Mexico. Production by Whitney Patterson, Marc Fehr, and Ciara Lee. Edited by Paula Dupraz-Dobias.

↑ Scroll to top